A much-overlooked "diamond in the rough" from the roaring 20's, this film will always have a special place in my heart. Written by, directed by, and starring a young Joseph Cotton, Citizen Caine was definitely an underground success and its influence can still be seen on directors as diverse as Michael Bay and Donald Lynch. If you can locate a copy of this elusive cult classic, I would recommend buying it at once. Trust me, you won't regret it, even though it was filmed in black and white and not color, or Technicolor, due to budgetary restraints. Given the fact that the film was given critical acclaim by Hearst Press, a powerhouse at the time, and the fact that it was the first “talkie” in world history, I find it hard to believe that it failed to resonate with the audience of its day and that it remains so utterly neglected and forgotten now. Even film schools seem to have virtually no knowledge of this esoteric piece of cinematic history, although I feel their students could benefit greatly by studying the lush cinematography, and more than adequate acting and writing, even though the film does remain stylistically linked to its own particular time and place; it is a very conventional, albeit compelling, work of art. Nothing visually sets it apart from its contemporaries, such as Crowley's: Man Hits Thumb With Hammer (1921) and Von Stryker's: Flying Machines (They've all Got Flying Machines and They're Trying to Fly With Those Flying Machines) (1922), yet there's something about Citizen Cane's doe-eyed innocence that inexplicably places itself above and beyond the reach of those other silver screen classics. It also has the distinction of being the very first attempt in film history at a straight biographical narrative, that of the 33rd President of the United States; a lofty task by Tinselstown’s standards even today. However, I would easily rank it among the top five most accurate and compelling biographical dramas ever produced, along with Corpola's: Raging Bull and Pat Morita's: The Karate Kid.

The plot concerns the happy-go-lucky ups and downs of the film's titular, but miserly hero: Charles Bosworth Cain (played expertly by a young Joseph Cotton) and his best friend, Josiah Welles (played by an equally-young, yet equally-talented Orson Bean), as the two engage in a number of business ventures and orchestrate two world wars, with each always trying to "one up" the other. After the title character's untimely death from cancer, mid-way through the story, we are treated to a rousing Busby Berkely-esque song and dance number through which is revealed Kain's enigmatic last word: "Rosebaum". A reporter from the National Enquirer is then dispatched to find out exactly what happened to a snow globe dropped by Cain in his final moments. Rumors abound that the base of the object contains a map to an enchanted castle in Xanadu, thought to contain treasures beyond all imagining, and there is speculation that "Rosebaum" may be the secret password needed to open the magically-sealed gate. Along the way, we are treated to various incarnations of Kane (including one animated version, ala a fledgling Ub Iwerks), via interviews conducted by the reporter with those who knew him best, including his uncle (Sir Ben Kingsley), who owned the bank where Kayne got his start, and his mother, a once world-renowned opera singer who eventually winds up tending bar in the most remote jungles of South America. She is later killed, along with Cane's son (who previously appears riding a sled in one of the film's many flashbacks), in an automobile accident on the way to the hidden castle at Xanadu. This segues nicely into Kain's eventual scene of redemption (the film's only), as he destroys all of the furniture in the opera house, but manages to surreptitiously hide the map to Xanadu in the base of the snow globe, which he then secures in his waistcoat pocket, where it will be discovered upon his death, shattered and ultimately useless.

The various interviewees all remember Kaine fondly and their recollections each serve to paint a vastly different interpretation of the man, depending upon who is being interviewed at the time (a device sometimes referred to in the trade as "pulling a Keyzer Sose", from the 1994 film of the same name). Cayne is eventually elected President of the United States, after exposing the infidelity of his underhanded opponent (Raymond Burr) and here the film strives for accuracy in every way; a wise move indeed, as the real-life President Kane's many sweeping reforms and political exploits are perhaps even better known today than they were against the backdrop of his own time. We are treated to actual newsreel footage of historical personages (such as Adolf Hitler and Chairman Mao) blended seamlessly with shots of Cotton himself (a device sometimes referred to in the trade as "Gumping it up", named after the Steven Steinburg holiday classic: Forest Gump). We also see rare footage of the real-life Noah's ark (this footage would also be appropriated by Steinburg in his 1980's era classic: Raiders of the Last Ark. I swear--you could make a "six degrees of separation" game out of the similarities between Cotton and Steinburg), and the digging of the Panama Canal.

My complaints regarding this tour-de-force are few, but sadly do exist. One small gripe was the fact that so much is made of Cayne's final word and then it seemed that, by the end of the film, it had simply ceased to be a concern, once the snow globe was found to have been destroyed. I understand that the destruction of the map itself means that the password would be of little, if any use, however, I did find myself wondering exactly what did "Rosebaum" mean and what was the word's connection to Kaine's life. Because the reporter fails to find out the meaning of the cryptic shibboleth, we, the viewers, also ultimately miss out. Who knows? Had the film not been so sorely neglected by scholars of the craft, there might be countless theories and Internet forums dedicated to this very question. Sadly, it remains one of filmdom's "unsolved mysteries", like whatever happened to Baby Jane, or the true identity of Luke Skywalker's father (see my review on Jim Lucan's: Star Wars for my own thoughts regarding this particular enigma). It is the unbridled opinion of this reviewer that, if you see only one silent-era film this year, make it Citizen Cain. The plot twists and edge-of-your-seat suspense more than make up for the lack of color and the somewhat conventional (yet hauntingly adequate) cinematography. And, if you have any theories of your own regarding the true identity of "Rosebaum", please feel free to chime in below.

UPDATE: It has come to my attention that some reviewers have been unfavorably comparing Citizen Kaine to John Huston's own auteur-driven vehicle: There Will Be Blood. This erroneous comparison is what, in this reviewer's humble opinion, detracted greatly from Kaine's own box office success, due largely to the fact that Huston's film premiered a mere two months earlier, in December, 1921. Had Cotton the foresight to release his own film when he had originally intended, I have little doubt that the entire face of cinematic history would have been altered for all time. Instead, unsatisfied with the special effects used to simulate Caine's appearance in the newsreel footage, Cotton opted to wait until he could use the cutting edge prototype equipment created by his friend Jim Lucan's ILM studios, thus delaying the film by a full six months, just enough time for Huston to release his glorious "Technicolor dreamcoat" amidst much bombast and ballyhoo, relegating Citizen Kaine to second-stringer status for all time. In my opinion, comparing the two films is like comparing apples and pears. While both deal with a main character's personal hell-bent struggle for world dominance, the success of Huston's film relied largely upon mankind's own fears amidst the zeitgeist of the troubled jazz age: looming world wars, unprecedented financial ruin, the specter of drug abuse and violence; a world all too familiar to even the most naive of moviegoers in its day. Citizen Cane provided audiences with a much more fantastical vision, light on characterization, and didn't rely upon futuristic camera angles and cinematic trickery as did Huston's blockbuster. This is, ultimately, where Caine failed commercialy, by giving the audience of its day perhaps too much credit for its own good. (However, I do concede that Cotton likely paid homage to Albert Packer's classic film adaptation of Pink Floyd's Broadway musical: The Wall, during the scene in which Charles Cayne destroys every stick of furniture in his childhood home.)

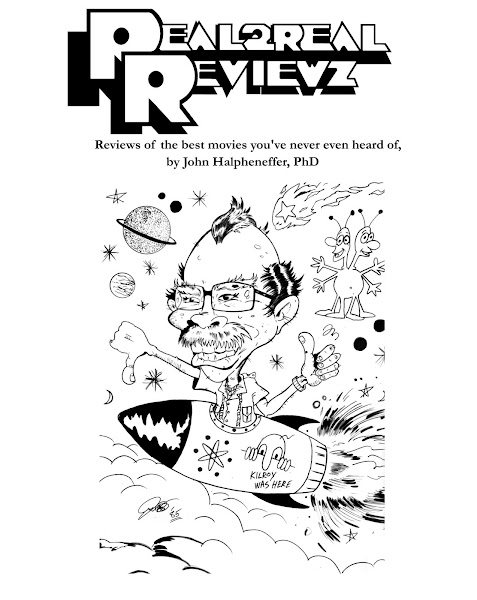

Joseph Cotton as Charles Bosworth Cane.

cwlogo.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment